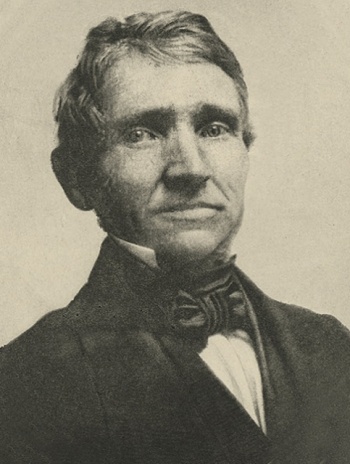

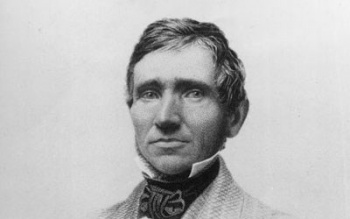

Charles Goodyear

Indice

Biografia

Charles Goodyear nasce a New Haven, nello stato del Connecticut (USA) il 29 dicembre 1800. A lui si deve la scoperta di un metodo per la vulcanizzazione della gomma.

« La vita non dovrebbe essere valutata esclusivamente dallo standard di dollari e centesimi. Io non sono disposto a lamentarmi per aver piantato semi di cui altri raccoglieranno i frutti. Un uomo ha da rammaricarsi solo quando semina e nessuno raccoglie. »

Questo personaggio si può definire come un vero, grande, appassionato della gomma. Goodyear era infatti convinto che questo materiale poteva divenire il materiale del futuro, destinato a rivoluzionare le abitudini di ogni attività umana. Indossava abiti di gomma, portava un bastone da passeggio di gomma, produceva sacchi per la posta di gomma e si fece fare addirittura un ritratto con la gomma.

All'epoca la gomma non era ancora in grado di soddisfare le esigenze per un suo impiego su larga scala, soprattutto perché questa se veniva esposta al calore fondeva; inoltre, a bassa temperatura, si rompeva, spezzandosi.

Charles Goodyear passò quasi tutta la vita ad eseguire migliaia e migliaia di esperimenti: la moglie Clarissa, stanca di questo stile di vita, spesso pregava il marito di porre fine ai suoi esperimenti, che non portavano mai a nulla di concreto, per cercare di convincerlo a sostenere la famiglia con qualsiasi altra attività che gli permettesse di guadagnare almeno qualche dollaro.

La famiglia Goodyear non navigava certo nell'oro: erano tanto poveri da dover spesso contare sull'aiuto dei vicini per riuscire a mangiare qualcosa quotidianamente. Capitò addirittura che alla morte di uno dei figli, senza soldi per pagare i funerali, fu lo stesso Charles a scavare la fossa per inumare la salma.

Un giorno dell'anno 1839 mentre Clarissa rincasava prima di quanto il marito prevedeva, Charles Goodyear interrompeva bruscamente uno dei suoi esperimenti. Per nascondere alla moglie la sua attività, aveva scelto in tutta fretta di riporre la miscela di gomma e zolfo nel forno. Più tardi avrebbe constatato che la sostanza era diventata sia resistente che flessibile: Goodyear aveva scoperto il procedimento che avrebbe lui stesso chiamato con il termine "vulcanizzazione".

La scoperta si può così riassumere: aggiungendo poche unità percentuali di zolfo al lattice ottenuto dall'albero della gomma, proseguendo poi con il riscaldamento della sostanza, si rende la gomma più elastica e più resistente ai solventi. La vulcanizzazione è un metodo che viene ancora oggi utilizzato nella produzione di pneumatici e altri oggetti di gomma.

Goodyear probabilmente non era molto portato per gli affari e brevettò la sua scoperta solo il 15 giugno del 1844. Durante questi anni intanto, altri si erano fatti avanti presentando richieste per brevetti analoghi: iniziò così un procedimento legale che si concluse nel 1852 e che vide Charles Goodyear vincitore contro i suoi rivali. Tuttavia alla fine della questione non fu in grado di pagare le spese processuali che ammontavano a più di 25.000 dollari.

Nel 1860 compì un viaggio a New York per andare a far visita alla figlia. Arrivato in città venne informato della morte della ragazza. Charles Goodyear non resse il colpo che la notizia gli provocò: morì il giorno 1 luglio 1860. Goodyear non ebbe mai benefici materiali derivanti dalla sua scoperta, lasciò anzi 200.000 dollari di debiti ai suoi eredi.

Va ricordato però che Goodyear conobbe alcuni momenti di gloria: nel 1851 fu invitato all'esposizione mondiale di Londra per presentare alcuni mobili e articoli casalinghi realizzati in gomma da lui. In occasione di un simile evento, in Francia, fu insignito della massima onorificenza, la Legione d'onore.

La notorietà del nome Goodyear ad oggi si deve all'azienda costruttrice di pneumatici che porta il suo nome e che lo ha reso famoso in tutto il mondo. L'azienda "Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company" fu fondata da Frank Seiberling 38 anni dopo la morte di Charles Goodyear.

Early life

Charles Goodyear was born in New Haven, Connecticut, the son of Amasa Goodyear, and the oldest of six children. His father was a descendant of Stephen Goodyear, one of the founders of the colony of New Haven in 1638.[4] In 1814, Charles left his home and went to Philadelphia to learn the hardware business. He worked industriously until he was twenty-one years old, and then, returning to Connecticut, entered into partnership in his father's business in Naugatuck, where they manufactured not only ivory and metal buttons, but a variety of agricultural implements. Marriage and early career

In August 1824 he married Clarissa Beecher. Two years later the family moved to Philadelphia, and there Charles Goodyear opened a hardware store. This is where he did most of his work. His specialties were the valuable agricultural implements that his firm had been manufacturing, and after the first distrust of domestically-made goods had worn away — for all agricultural implements were imported from England at that time — he found himself heading a successful business.

This continued to increase until it seemed that he was to be a wealthy man. Between 1829 and 1830 he broke down in health, being troubled with dyspepsia. At the same time came the failure of a number of business houses that seriously embarrassed his firm. They struggled on, however, for some time, but were finally obliged to fail.

Between the years 1831 and 1832, Goodyear heard about gum elastic and very carefully examined every article that appeared in the newspapers relative to this new material. The Roxbury Rubber Company, of Boston, had been for some time experimenting with the gum, and believed it had found means for manufacturing goods from it. It had a large plant and was sending its goods all over the country. It was some of Roxbury's goods that first attracted Goodyear's attention. Soon after this, Goodyear visited New York, and his attention went to life preservers, and it struck him that the tube used for inflation was not very effective nor well-made. Therefore, upon returning to Philadelphia, he made some tubes and brought them back to New York and showed them to the manager of the Roxbury Rubber Company.

The manager was pleased with the ingenuity that Goodyear had shown in manufacturing the tubes. He confessed to Goodyear that the business was on the verge of ruin, and that his products had to be tested for a year before it could be determined if they were perfect or not. To their surprise, thousands of dollars worth of goods that they had determined to be of good quality were being returned, the gum having rotted, making them useless. Goodyear at once made up his mind to experiment on this gum and see if he could overcome the problems with these rubber products.

However, when he returned to Philadelphia, a creditor had him arrested and imprisoned. While there, he tried his first experiments with India rubber. The gum was inexpensive then, and by heating it and working it in his hands, he managed to incorporate in it a certain amount of magnesia which produced a beautiful white compound and appeared to take away the stickiness. He thought he had discovered the secret, and through the kindness of friends was enabled to improve his invention in New Haven. The first thing that he made was shoes, and he used his own house for grinding, calendering and vulcanizing, with the help of his wife and children. His compound at this time consisted of India rubber, lampblack, and magnesia, the whole dissolved in turpentine and spread upon the flannel cloth which served as the lining for the shoes. It was not long, however, before he discovered that the gum, even treated this way, became sticky. His creditors, completely discouraged, decided that he would not be allowed to go further in his research.

Goodyear, however, had no mind to stop here in his experiments. Selling his furniture and placing his family in a quiet boarding place, he went to New York and in an attic, helped by a friendly druggist, continued his experiments. His next step was to compound the rubber with magnesia and then boil it in quicklime and water. This appeared to solve the problem. At once it was noticed abroad that he had treated India rubber to lose its stickiness, and he received international acclamation. He seemed on the high road to success, until one day he noticed that a drop of weak acid, falling on the cloth, neutralized the alkali and immediately caused the rubber to become soft again. This proved to him that his process was not a successful one. He therefore continued experimenting, and after preparing his mixtures in his attic in New York, would walk three miles to a mill in Greenwich Village to try various experiments.

In the line of these, he discovered that rubber dipped in nitric acid formed a surface cure, and he made many products with this acid cure which were held in high regard, and he even received a letter of commendation from Andrew Jackson. Exposure to harsh chemicals, such as nitric acid and lead oxide, adversely affected his health, and once nearly suffocated by gas generated in his laboratory. Goodyear survived, but the resulting fever came close to taking his life.

Together with an old business partner, he built up a factory and began to make clothing, life preservers, rubber shoes, and a great variety of rubber goods. They also had a large factory with special machinery, built at Staten Island, where he moved his family and again had a home of his own. Just about this time, when everything looked bright, the panic of 1837 came and swept away the entire fortune of his associate and left Goodyear penniless.

His next move was to go to Boston, where he became acquainted with J. Haskins, of the Roxbury Rubber Company. Goodyear found him to be a good friend, who lent him money and stood by him when no one would have anything to do with the visionary inventor. A man named Mr. Chaffee was also exceedingly kind and ever ready to lend a listening ear to his plans, and to also assist him in a pecuniary way. About this time it occurred to Mr. Chaffee that much of the trouble that they had experienced in working India rubber might come from the solvent that was used. He therefore invented a huge machine for doing the mixing by mechanical means. The goods that were made in this way were beautiful to look at, and it appeared, as it had before, that all difficulties were overcome.

Goodyear discovered a new method for making rubber shoes and received a patent which he sold to the Providence Company in Rhode Island. However, a method had not yet been found to process rubber so that it would withstand hot and cold temperatures and acids, and so the rubber goods were constantly growing sticky, decomposing and being returned to the manufacturers.

Vulcanization trials

In 1838, Goodyear met Nathaniel Hayward in Woburn, Massachusetts, where Hayward was running a factory. Some time after this Goodyear himself moved to Woburn, all the time continuing his experiments. He was very much interested in Hayward's sulfur experiments for drying rubber. Hayward told Goodyear that he had used sulfur in rubber manufacturing. The circumstances attending the discovery of his celebrated process is thus described by Mr. Goodyear himself in his book, "Gum Elastic and Its Varieties, with a detailed account of its application and uses and of the Discovery of Vulcanization." Perhaps showing humility, or following scientific convention, Goodyear used only third person references when speaking about himself. Or perhaps he did not want people to think he was bragging and wanted their truthful opinion.

Some say (Damian Francis Mullin, circa Feb 1865) that Goodyear tried the experiment with a similar material over an open flame, and saw that the gum elastic was charred, but on the edge of the charred areas were portions that were not charred, but were instead perfectly cured. Other sources claim that Goodyear accidentally spilled the rubber mixture on a hot stove. The key discovery was that heating natural rubber and sulfur created vulcanized rubber. This process was eventually refined to become the vulcanizing process. The inventor himself admitted that the discovery of the vulcanizing process was not the direct result of the scientific method, but claims that it was not accidental. Rather it was the result of application and observation.

Now that Goodyear was sure that he had the key to the intricate puzzle that he had worked over for so many years, he began at once to tell his friends about it and to try to secure capital, but they had listened so many times that his efforts were futile. For a number of years he struggled and experimented and worked along in a small way, his family suffering with himself the pangs of the extremest poverty. At last he went to New York and showed some of his samples to William Ryder, who, with his brother Emory, at once appreciated the value of the discovery and started manufacture. Even here, Goodyear's bad luck seemed to follow him, for the Ryder Bros. had failed and it was impossible to continue the business. Perfection and Patent of Vulcanization in Springfield, Mass.

United States patent 3633

Several years earlier, Goodyear had, however, started a small factory at Springfield, Massachusetts, to which he moved his primary operations in 1842. The factory was run largely by Nelson and Henry Goodyear, Charles' brothers. Charles Goodyear's brother-in-law, Mr. De Forest, who was a wealthy woolen manufacturer, took Ryder's place. The work of making the invention practical was continued. In 1844, in Springfield, the process was sufficiently perfected that Goodyear felt it safe to take out a patent. The first vulcanization of rubber is considered one of the major "firsts" that contributes to the City of Springfield's nickname, "The City of Firsts." [5] In 1844, Goodyear's brother Henry introduced mechanical mixing of the mixture in place of the use of solvents.

Court cases regarding vulcanization

In the year 1852 Goodyear went to Europe, a trip that he had long planned, and saw Thomas Hancock, then in the employ of Charles Macintosh & Company. Hancock claimed to have invented vulcanization independently, and received a British patent, initiated in 1843, but finalized in 1844. In 1855, in the last of three patent disputes with fellow British rubber pioneer, Stephen Moulton, Hancock's patent was challenged with the claim that Hancock had copied Goodyear. Goodyear attended the trial. If Hancock lost, Goodyear stood to have his own British patent application granted, allowing him to claim royalties from both Hancock and Moulton. Both had examined Goodyear's vulcanized rubber in 1842, but several chemists testified that it would not have been possible to determine how it was made by studying it. Hancock prevailed. Despite his misfortune with patents, Goodyear is claimed to have said, “Life should not be estimated exclusively by the standard of dollars and cents. I am not disposed to complain that I have planted and others have gathered the fruits. A man has cause for regret only when he sows and no one reaps.” Death and legacy

Goodyear died July 1, 1860, while traveling to see his dying daughter. After arriving in New York, he was informed that she had already died. He collapsed and was taken to the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City, where he died at the age of 59. He is buried in New Haven at Grove Street Cemetery.[6] In 1898, almost four decades after his death, the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company was founded and named after Goodyear by Frank Seiberling.[7] On February 8, 1976, he was among six individuals selected for induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.[8] In Woburn, Massachusetts, there is an elementary school named after him.[9] The city of Goodyear, Arizona was named after Goodyear.

http://biografieonline.it/biografia.htm?BioID=2126&biografia=Charles+Goodyear